2016 to 2017From both a racing and a coaching perspective, 2016 was spectacular! My athletes and I raced well and, importantly, progressed in our journeys as athletes. I have continued my lifelong process of learning as a coach, and I am confident when I say that I am a better coach than I was a year ago.

As an athlete, it is common practice to look back on my personal racing for the year. I’m not going to list all my race results, for those interested, they can be found here: http://www.fordituderacing.com/about.html But when I look at the year as a whole, what I see is: if I raced, I was on the podium (with one exception at Kona). That includes 5x 70.3 (half Ironman) age group podiums 1x full Ironman race (1st) Ranked 3rd in the world for my age group at the 70.3 distance Gold level (top 1%) All World Athlete for Ironman All American for USAT (USA Triathlon, top 10%) I start 2017 having qualified for and planning to race the World Championships for both the 70.3 (half) and full Ironman distances. I’m looking forward to another chance at Kona! Looking back at my training for the year, I have done more training volume than I ever have before. Ballpark figures include: Swimming: 306 miles, 165 hours Biking: 7863 miles, 464 hours Running: 1934 miles, 274 hours For a total of: 903 hours of training, not including other activities such as strength training or stretching. This is the million mile overview. It doesn’t show what I did during that time, how that training was structured, what I did during those workouts, or how I recovered. All of those details are critical, and that’s what the art of coaching is about. But, it is interesting to note that the number of training hours is closely correlated to the level competition at which an athlete competes. When looking at athletes in beginner, age group contender, age group elite and pro divisions, the number of hours they train generally falls into distinct categories. I’m not going to provide those numbers, because the tendency is for people to decide to train at the hours of the category they want to join, ignoring whether they are ready for that training volume and what that training should look like. Increasing training volume is a very long term project. Suffice it to say that my training falls in line with the published categories of results, and my volume of training is not unique. This is a long way around for me to talk about consistency. Yes, I took planned breaks during 2016. And yes, I took unplanned breaks when I got sick or injured (http://www.fordituderacing.com/blog/what-i-learned-from-falling-on-my-head). So that means that those hours were accumulated all the rest of the time. There were no long breaks, or long periods of minimal training. It reflects a lot of day in, day out putting in a lot of hours every day, whether I was in the mood or I wasn’t. Consistency is not sexy, and it does not look impressive to someone watching. It isn’t monster workouts or drilling oneself into oblivion, or putting most of the week’s mileage into the weekend. Consistency is about staying healthy and getting all the workouts done, the big ones and the little ones. It is about making time for all those workouts, and making them a priority. Consistency is the single most powerful force in triathlon training. It is what makes it possible to do more this year than you did last year, and that is how you gain the ability and earn the right to do more the following year. Success is not a short term project. It is a far longer term project that most people realize. It requires not just long term participation, but long term consistency, dedication and progression, for many years. Most people like the idea, until they have been doing it several months and get impatient wanting results, or tired of the daily grind of doing the workouts and prioritizing them in their lives. Then people get frustrated and quit, or decide to increase their volume or intensity too quickly and get injured, or commonly: yo-yo back and forth between getting it done and not getting it done, failing to progress as an athlete, and feeling frustrated and disappointed. In conclusion: yes, that 30 minute run or short swim matters. Do it. Every workout is there for a reason. Missed workouts means a delay, or even a setback in progression, as you cannot build upon workouts that aren't completed. Set big goals understanding the time commitment required and with a realistic understanding of whether it fits into your life. Workouts will be designed to progress you on your path toward your goals, but do not focus on your big goal. Instead, focus daily on the goal of doing all your workouts today. Then, daily, string the days together into weeks, the weeks into months, and the months into years. All you have is today. Whatever your dreams may be, if you progress as an athlete from year to year, your triathlon journey will be personally fulfilling and rewarding….and there is no greater award or reward than that. Part 1:Ironman World Championship Kona, Hawaii  10 years. OK, 10 years minus one month. That’s the length of time between the completion of my first Ironman in Florida in 2006 (with the dream of Kona), and my first Ironman World Championship race as a qualifier (I competed in 2012 on a legacy slot). Kona 2016 was to be my 22nd full Ironman, and the culmination of a decade long goal. To say that this race became monumental in my mind is something of an understatement! And therein lies the problem. I qualified a full 13 months in advance, and that gave me plenty of time to stress and prepare. Unfortunately, I did more stressing than necessary, and less preparing than necessary. Don't get me wrong, I did a whole lot of preparing; I got a new bike, visited the wind tunnel, chose my kit, helmet, bottle location, and practiced my fueling in 5 half Ironman (70.3) races. I had nailed my mental game in my qualifying race, after getting help from a sports psychologist, but then neglected to keep up the practice. I left cards on the table that I should not have. Things just got busy. I trained a lot. Life got complicated. My dog got sick, and stayed sick. I took on too much work. I neglected my meditation time. I raced all year on a wheelset that worked well for me, but would not work in Kona, and didn’t think of that until the last minute, then scrambled to change hubs and to transport them to the island. I failed to think about how my fueling plan needed to change for the Big Island. I was afraid. I was afraid of the crosswinds, the external pressure, and my gear questions. I was afraid that this might be my only chance to prove myself at this race; after all, it took me a long time to get there, requalifying was not a given. My previous experience in Kona had landed me in the hospital in a blackout from hyponatremia, so that was scary. I felt out of control. My bike had mechanical problems, and was only partially fixed by the time it had to be shipped. Things got so busy that I hit the ground running every morning as hard as possible to barely get done what had to be done. I was tired. But I thought that once I flew to Hawaii, it would get better. It didn’t. The bike mechanical problems multiplied. I took the bike to a shop 6 times in the first 4 days. I drove out to the worst winds on the course to try different wheels, and found the winds to be as difficult as I remembered. I spent a lot of time trying to solve these problems instead of resting or eating. I wasn’t sleeping, because of jet lag, stress, and a hot, noisy bedroom. My stress level rose until all the people around me could clearly see it, and since I had not been practicing my mental strategies regularly, my efforts to bring my stress levels down weren’t working. Until it all came crashing down, literally, 5 days before the race. I got up in the middle of the night to get something to eat and passed out, hitting my head on the tile floor. And that’s what it takes to give me an attitude adjustment. I returned to consciouness on the floor and knew I was in trouble. I got checked out at the ER (can I please go to Kona without going to the ER??) They couldn't find a medical reason, but I knew the reason. I had lost the mental game before the race even started. Now I was in salvage mode. Paradoxically, I felt a huge sense of relief.  Gone were my expectations. Gone was the external pressure. I just needed to get to the start line, and then to the finish line, and at this point, getting to the start line was not a given. So, I took any course that led to less stress, even if it meant giving up time in the race. I chose the most conservative wheels, an extra bottle cage on the bike, whatever it took to decrease my fears and stress. I took time off, whether my schedule called for it or not, I found ways make my environment more conducive to sleep, I meditated, had fun, and I ate (a lot!). Race day arrived, and I was thinking and making good decisions. Ironman is a race of patience and good decision making, so that’s critical. I got tested early – as I got ready for the swim, the zipper on my Roka swim skin failed. I borrowed a cell phone and called Ivan to run back to the condo for my TYR skin, as the women filed toward the start. There was a surreal moment, when all the women were lined up in the water to start, and I stood on the stairs leading into the water with the CEO of Ironman, Andrew Messick, looking for Ivan in the crowd. Finally I pulled up my sleeved tri suit, which isn’t made for swimming, and got in the water. It is what it is, and I would make the best of it, without getting upset. Win!  The swim went smoothly; I was in a good group of women, although it got broken up when we had to swim around some pushy slow men who’d had a head start. I chafed pretty badly from the suit, but no surprise there. T1 was methodical and careful. On to the bike! Kona is a unique beast. The swim, the bike and run are each very challenging, as opposed to other races. There is also a huge difference in the race dynamic. Surrounded by the best in the world, people used to being in the front of the field find themselves in the middle, or the back, and that’s where I found myself. Luckily for me, I’d already had my attitude adjustment in the condo, so I just settled in, and prepared to tackle my fears of the wind. With my conservative gear choices, I found the side winds that had scared me so much were manageable. Head winds are annoying, but I can practice those at home. Because the amateur women start in the last of 4 waves, we get the worst of the heat and winds on the bike course, and at mile 70, I was digging into those headwinds and beginning to get tired.  There is another problem with being last to start that I had not considered. At mile 80, the aid stations ran out of water. I found myself tiring, riding into a head wind, in crazy heat and humidity, looking at piles of empty bottles on the side of the road, with no available water. My plan involves carrying everything I need (concentrated Skratch drink and Skratch Fruit Drops), but water is required for both my fluid and calories. I did not see a good way out of this problem. I could try the Gatorade, which I knew would wreak havoc on my GI tract, or go dry and see if the next aid station had water. I went for option 2. It would have worked, except that between mile 70 and 112, there ended up being only 1 aid station that had water left for the amateur women’s race. Trying to manage my emotional response to being left dry at the World Championships, a race with a $1000 entry fee, was difficult. It was also scary, considering that I had been hospitalized the only other time I had competed here, and going without fluid in high heat and humidity carried a medical risk. But I soldiered on. I rode into T2 with a brake dragging and squealing on my bike, and with gut cramps, but upright. I started the run at a walk, waiting for my gut to settle, and getting what I needed. That turned into a run, and I walked the aid stations. My legs never came online, but things did pull back together somewhat, and mentally I was savoring the experience of the World Championship race, and grateful to be there. I got out onto the Queen K highway, and then met the unthinkable – the run aid stations were out of water. There was none at mile 14, and they announced that all stations were out. At that moment, I truly did not know how this would end, and I worked to stay calm. Luckily, the announcer was wrong, and subsequent stations did have water.

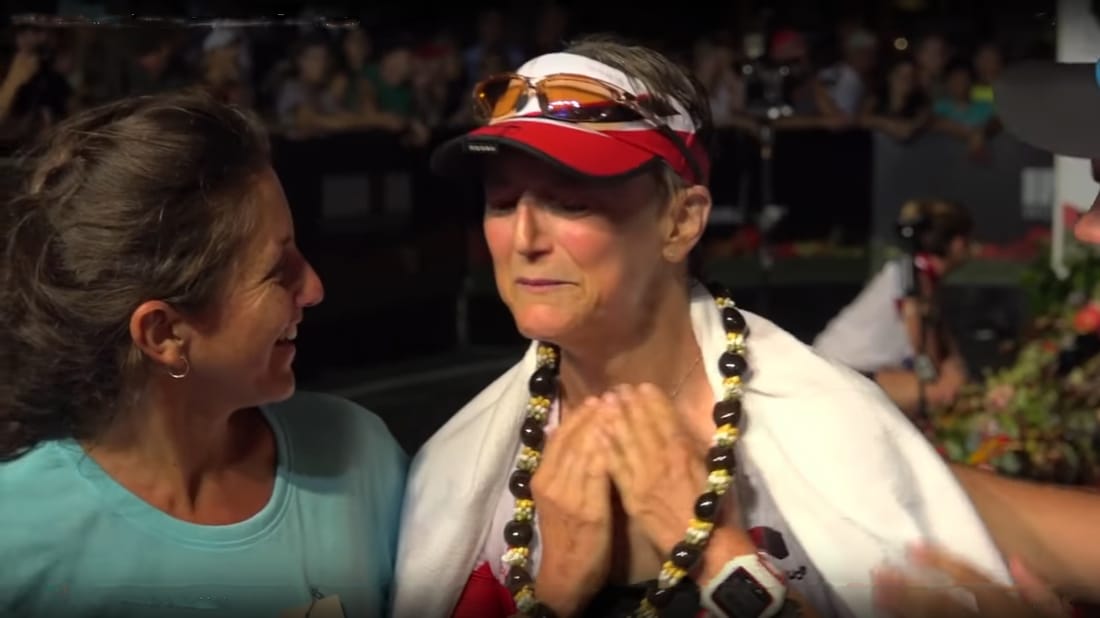

I was grateful, but I wanted another chance at this course! Would I ever get it? Would it take another 10 years? I knew I had not achieved what I am capable of, and wanted to try again. In that way, my performance goals act as a driver. Part 2: Ironman Arizona 2016  6 weeks later, I toed the line at Ironman Arizona. I didn’t hide the fact that I was racing, but I didn’t announce it or talk about it much. That allowed me to decrease the external pressure I created for myself. I warned people around me not to place expectations on the race. I methodically worked out every detail prior to the race, and made every decision before making the trip. I worked on my mental game and meditated daily. I focused on getting sleep and eating in the days leading up to the race. Life got less stressful when the dog got diagnosed with cancer, had the tumor and some intestine removed, and finally got better. I decreased my workload. I was preternaturally calm on race morning. I focused on my task, executed a very patient race, and got it done….winning my age group, and punching my ticket for Kona 2017. It shows that you cannot win a race on mental fitness alone, but you surely can lose it. So I have another chance! Kona does not frighten me now, although it has my deep respect. The course itself is the greatest competitor I have ever faced, and it requires me to be my best self. I know I have the ability to perform at a higher level than I have. To do that, I have to do more than physically prepare. I have to become a better me.

Many thanks to my coach, Brian Stover of Accelerate 3, Skratch labs, Torhans, ISM saddles, my husband, and the village of support people who make my success possible! On the heels of my last blog post about wrecking my bike in a race and getting up to win, there have been some misconceptions that I need to clarify.

Last month in an Olympic triathlon, I was passing a guy on the bike who veered into me. My bike went out of control, but I was able to get it off the road before the bike stopped in a ditch, and I ejected like a javelin, head and shoulders first, into the dirt. I spent nearly 3 minutes out of the race before getting up to win. What I failed to describe is: What happened in that 3 minutes? To explain, first I must go back farther to another race: the Ironman World Championship in Kona, Hawaii in 2012. I was there on a slot through the legacy program, which is set up for people who have done at least 12 Ironman races, but who have not qualified. To the best of my knowledge at the time, this might be the only chance I ever had to compete at this race. Things were not going well from the beginning. I had a subpar swim, and couldn’t hold my goal watts on the bike from the start. I accepted this, adapted my goals, and developed the mantra “Preserve the Finish”. I did everything I knew to make sure that I finished the race. Sometimes what gets you is what you do not know. I had a major flaw in my nutrition plan, both leading into and during the race. In retrospect, it is one that plagued me at every race up to this one (and the one that led to my future use of Skratch Labs products) – I sweat a lot, and I lose a lot of sodium in my sweat. I had diligently stayed hydrated with water up to the race, and I was drinking water on the bike, supplemented with salt pills….but not enough. Things got worse. I was vomiting on the bike. I spent 20 minutes in T2 (2nd transition from bike to run) with cramps, waiting until I felt I could safely stand without medical personnel pulling me off the course. The marathon went from running, to walking, to moving in and out of a blackout. I was confused and didn’t recognize my roommate (who was uniquely recognizable as an amputee). I continued to focus on my “need” to finish the race. I knew I was in trouble, but I did not realize how much trouble I was in. I crossed the finish line, and have no memory of it. I was taken to the medical tent with dangerously low sodium levels. There is some evidence that it was 116 (things are unclear). After several hours, they got it up to 118, and sent me to the hospital for further treatment. Hyponatremia is defined by a sodium level less than 135, profound hyponatremia is defined at less than 125 and has a high mortality rate. The brain swells, you can have seizures, coma, the brain can herniate through the foramen magnum, and death. When I became cognizant the following morning, I looked at my husband and commented, “You seem awfully calm about this.” His response disturbed me. He said, “I have come to accept the fact that you may kill yourself doing this, and there is nothing I can do about it.” I was not OK with that on any level. It was then that I (finally) realized that as much as I love my sport, and as competitive and driven as I am, that I am not willing to die for it. Preserving my life and my ability to race is more important that any finish. So, what happened in that 3 minutes in the Olympic race? Once I ascertained that I had not broken my neck and could move, my mental process was this: There were 2 options, and both were equally acceptable. I could go on and race, or I could drop out and accept a DNF (did not finish). The deciding factor would be my physical state, NOT what anyone else thought then or later. I spent that time evaluating myself. Admittedly, that can be hard any time your brain may be involved with the damage. However, I had some concrete things to hang my hat on: most people know that I have a degree of face blindness; I have trouble recognizing faces as well as remembering names. At the scene of the wreck was someone I knew, but not well, and he was supposed to be racing. I saw him, recognized him out of context, and asked him what he was doing out of the race by name. I was able to reassemble my helmet, bike and gear. In those 3 minutes, I assessed my condition, saw zero signs of head trauma, and made the choice to continue the race. I could have just as easily chosen to walk off the course. I also considered my long term goals – in 7 weeks I would be racing Kona again (as a qualifier), and did not want to endanger that race; but if things were ok, I wanted the workout effort for training purposes. “Death before DNF” is a damaging and dangerous motto. Dropping out of a race can be the single most difficult and courageous move an athlete can make. I am not suggesting that one should give up whenever the going gets tough, but there are plenty of opportunities in this sport to “prove” our mental and physical toughness without endangering our life or our ability to continue to train and race. We are driven people, and we invest a lot in the outcome of each race. To achieve our biggest goals, we must have the strength to do “whatever it takes” that will allow us to continue to consistently train and race – “whatever it takes” includes walking off the race course or away from a training session when it is in our best long term interest. "What I Learned from Falling on my Head"

I decided to do a small local Olympic triathlon as a C priority race, well maybe a D priority race (if there is such a thing), one week after an Ironman 70.3 as a social event with friends from the newly minted Cookeville Triathlon Club. I figured it would make a good workout, and if I got lucky, maybe I could hit the overall podium on tired legs. I started in the last wave, and by the swim exit, things were going well as I had swum through the women’s wave ahead of me, into the men’s wave. Less than a mile into the bike, I was in my aerobars going 20-30mph passing a guy, who suddenly swerved into my path. I was able to get one hand out of the bars onto my rear brake, and managed to guide my fishtailing bike off the road, figuring it would make a softer landing, since it was clearly going down. It was a good plan, until a ditch stopped the front wheel cold and I flew over the bike onto my head. I never put out a hand. I found myself lying face down, with my neck in an unnatural position, wondering if I’d broken my neck. After I found out that body parts still worked (but not fully aware of the damage until that evening), I got up, and picked up the gear spread over a swath of territory. I put it all back together, wondering, “what now?” I didn’t see reason to stop, so I got back on the bike, and resumed the race. There was a moment in which I thought that my idea of the overall podium was gone, but then I forgot about that outcome goal, and focused on the process of racing instead – dealing with the fact that I’d lost half my nutrition, my helmet wasn’t on my head quite right, the visor was sideways, and watching my effort and my body for signs of trouble. At one point, I found myself being pissed at the guy who took me down (and didn’t stop), but then I told myself that “I’m so strong, it’s appropriate that I be given a time handicap. Let’s see what I can do!” That served to refocus me from the unfortunate past to a confident present. In the end, after 3 minutes lost to the wreck, I won the race overall. I’m proud of that result. Not because of the outcome, because that reflected the strength of the field more than my own strength. And not because I physically got up and raced, because I’ve proven in the past that I’ll keep racing even when I shouldn’t. I’m proud of the way I managed it mentally. In the past, when things went badly in training or racing, I’ve had a tendency to have a part of me fear failure, give up, and go to a black mental hole. I’ve been in that hole for most of an Ironman bike and the whole marathon. That’s a long time, and it is not a pretty place. I’ve procrastinated the hardest workouts for fear of failing. So how did I get from there to here? I practiced failing. You’d think that failing in training would bring on the black hole and a sense of, “Why try, I’m going to fail anyway”, and it can, if you focus on the failed performance goal. I’ve been chasing some power numbers on the bike in intervals that are a little out of my reach. At first it was pretty discouraging. Then I realized that the whole purpose of reaching those numbers was not so much to achieve them, but to engage the process of going as hard as I could. In the dark space of those intervals I’d ask myself, “Can you go harder?” I checked for ragged breathing, burning legs, and involuntary grunting. If they weren't there, I pushed harder. If I finished the interval breathing hard, with quivering legs, sweat and snot and spit everywhere, well, then I put out an effort that stimulated the physiologic changes I’m seeking, no matter what the numbers say. That’s the real goal. And if I reach for that process goal, the numbers will come, and I see them coming. One day I will achieve that performance goal. And the performance goals will lead to my outcome goals. So, when I fell on my head, it didn’t matter how it all came out. It only mattered that I got up and tried, and didn’t allow my mind to distract me from that one thing. That was mental fitness that I had learned and practiced in training. There are probably easier ways to learn this lesson, but some of us need a good smack on the head from time to time….. Welcome to my webpage and my first blog post! I started big. I chose a photo of molten lava as the header for this section, because lava is creation in its rawest form - the creation of new earth. The photo on my articles page (also below) shows the power of the ocean on lava rock, a force which requires change, destruction and new creation. I took both these pictures on the east side (Hilo side) of the big island of Hawaii during my last visit there.

My logo also combines elements of lava and waves. The word fortitude is from the root fortis, Latin for strong, and is defined as courage in pain or adversity. Synonyms include courage, bravery, endurance, resilience, strength of mind or charactor, spirit, grit and guts. Forditude is a play off my name and the word fortitude. These powerful symbols, combined with an attitude of fortitude, symbolize inevitable change and power. I am fascinated by the forces that create and change us as people. Sport has that power. It tears down our barriers, bring us to our most raw core, and recreates us as a new, stronger person. Once you have faced your fears, addressed your weaknesses, been uncomfortable, and discovered that your limits are far beyond what you imagined them to be, you encounter life on a whole new level. Sport enhances life. Similarly, finding peace in our daily lives, living honestly and with integrity, dealing with others with patience and compassion, and being in touch with the moment and the experience you find yourself in right now enhances sport. Learning to listen to yourself, to hold your own self in compassion without judgement, and to appreciate the moment, is a tool that enhances not only daily life, but training and racing as well. In this way, sport cannot be separated from life. The creative forces of one transforms the other. Sometimes quickly with extreme heat, other times slowly by wearing down. Change is life. "Wheresoever you go, go with all your heart." Confucius Chinese philosopher & reformer (551 BC - 479 BC) |

AuthorSusan Ford is a coach, triathlete and veterinarian who enjoys sharing life with others. Archives

January 2017

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed